Category: Sin categoría

Gravity

Uncertainty

EDCA–Quantum Uncertainty

In EDCA, cells change only when energy arrives. Energy “spots” expand as wavefront shells and collapse on ready cells. If you force collapse to one site, you learn position perfectly but you lose direction/spin information. If you allow many candidates (e.g., a ring detector), collapse statistics reveal direction/spin — but position becomes uncertain. This is an EDCA-native uncertainty principle: a measurement tradeoff built into readiness-gated collapse.

Abstract

Energy-Driven Cellular Automata (EDCA) separate readiness from transition: a cell can satisfy local rules and still not change until energy arrives. Energy is carried by mobile quanta (“spots”) that propagate outward as wavefronts and collapse only when they intersect transition-ready sites. When multiple ready sites are available at the same time, collapse is resolved by a selection rule that depends on wavefront geometry (privileged distance), spot spin (a directional bias carried by the spot), and allocation density ρ (how space is instantiated).

This article explains—without heavy mathematics—how an uncertainty-principle-like limitation naturally emerges in EDCA. The key is simple: you cannot measure position perfectly and direction perfectly at the same time, because those two goals require incompatible readiness configurations.

1) EDCA in one idea: readiness is not enough

In classical cellular automata, the rules directly determine the next state. In EDCA, something more physical happens:

- The rules can say “this cell is ready to be born” or “this cell is ready to die.”

- But nothing changes until an energy spot arrives.

So EDCA has two layers: (1) logical readiness and (2) physical transition triggered by energy arrival. This structure makes EDCA naturally “measurement-like”: spots spread like waves, collapse triggers discrete events, and collapse outcomes depend on the environment.

2) Wavefront shells: why distance and spin are complementary

A spot emitted from a source does not travel as a classical particle. It expands as a wavefront: in 2D you see a growing circle; in 3D a growing sphere. At any moment, the wavefront forms a shell at radius r.

This implies a crucial point: many candidate sites can be at the same privileged distance because the wavefront is circular/spherical. Therefore distance and spin are not competing forces:

- Distance gates eligibility (which shell is “active” now).

- Spin selects among candidates within that shell (which site wins the collapse).

3) What “direction” means in EDCA

In EDCA, a spot is not a point particle with a trajectory. So “direction” is not classical velocity. Instead, direction is defined operationally:

Direction is the bias pattern the spot applies when it must choose among multiple ready candidates on a shell.

This bias is governed by the spot’s spin vector. Positive spots prefer more aligned candidates; negative spots prefer less aligned candidates (by definition). So “measuring direction” means building a detector where many candidates exist simultaneously and reading the statistics of collapse outcomes.

4) A 2D grid snapshot (why multiple candidates exist naturally)

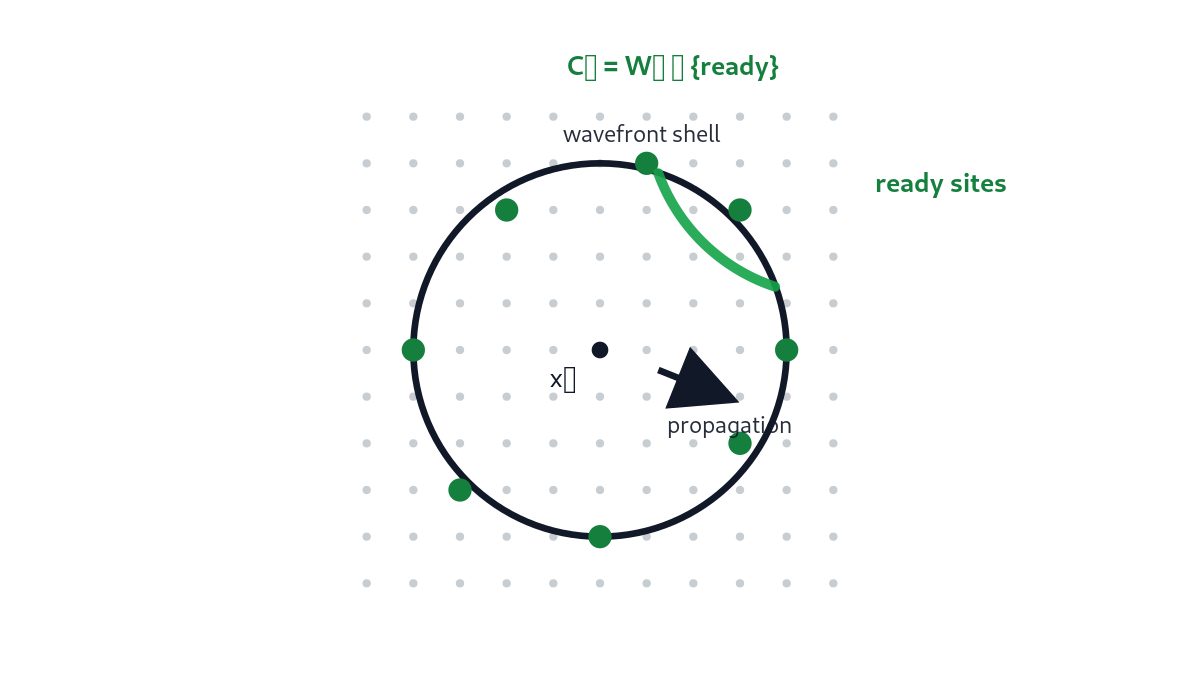

Figure 1 shows the most basic EDCA measurement geometry in a 2D slice: a wavefront shell intersects a set of ready sites. If exactly one site is ready, collapse is forced. If multiple are ready, the spot must choose, and spin can bias that choice.

5) Two detectors: the simplest proof of EDCA uncertainty

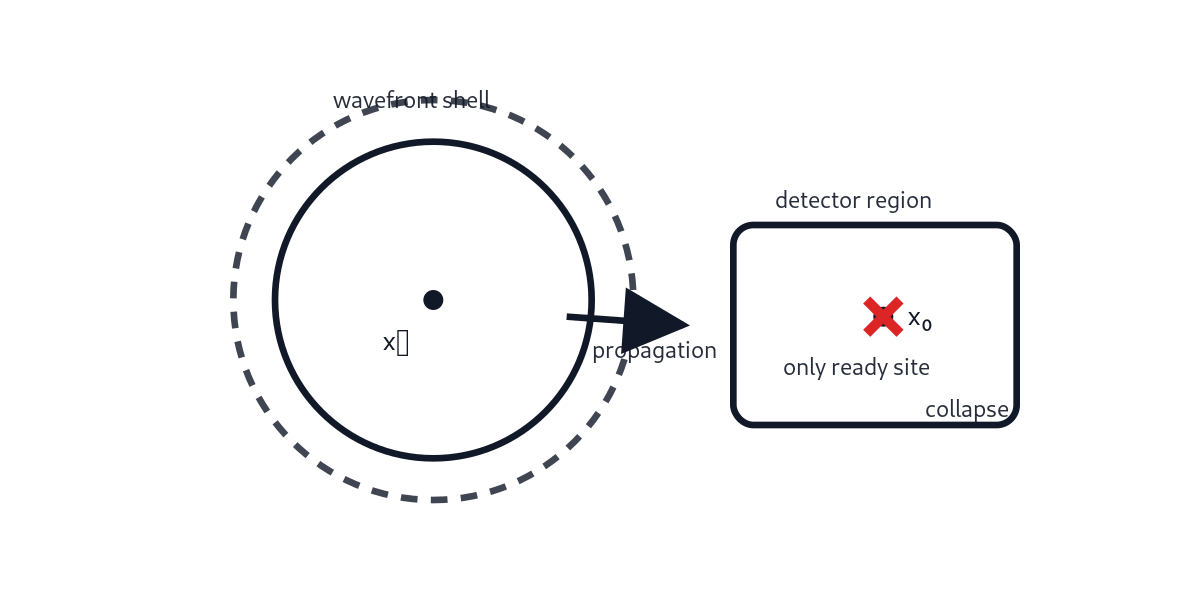

Device P: single-site readiness gate (perfect position)

If you engineer readiness so that only one site is ready when the wavefront arrives, collapse happens at that site every time. You learn position perfectly. But since there is no competition, the outcome cannot depend on spin.

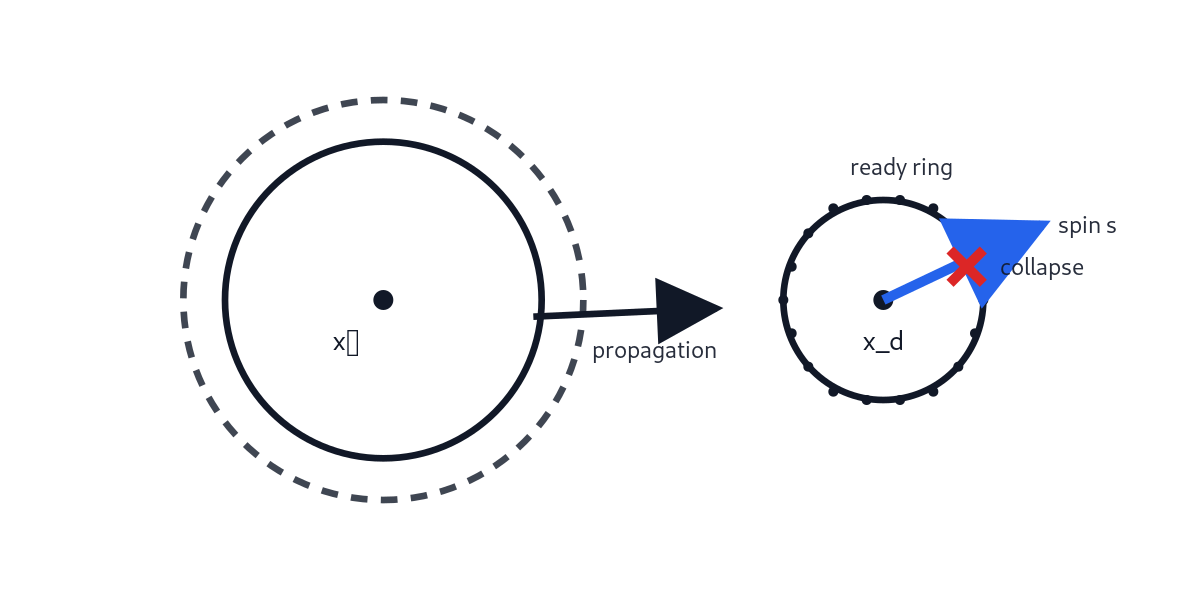

Device R: ring/shell detector (direction becomes measurable)

If you engineer readiness into a whole ring (2D) or shell (3D), many candidates are ready at once. Collapse becomes probabilistic across the ring, and the distribution depends on spin. Repeating the experiment lets you infer direction statistically — but now position is uncertain across the ring.

6) The EDCA uncertainty principle (in one sentence)

If you force collapse to one site, you know position perfectly but you eliminate direction/spin information. If you allow many candidates so that direction/spin is inferable, position becomes uncertain.

7) Where λ fits

The EDCA parameter λ controls how sharply distance gates collapse. In shell language:

- Large λ → thin shell band → more precise radial collapse.

- Small λ → thicker band → more radial blur before collapse.

This does not compete with spin. λ defines how “thick” the active shell is; spin selects within the shell.

8) Simple scaling intuition

Without heavy math, the scaling is intuitive:

- Position uncertainty grows with detector size: a ring detector of radius R gives roughly Δx ~ R.

- Direction uncertainty shrinks with detector size and spin strength: larger R and stronger spin bias β give sharper directional preference.

9) Polarity flip = built-in measurement back-action

EDCA includes polarity flip: + becomes − after enabling a birth, and − becomes + after enabling a death. Because polarity reverses the spin preference, collapse is not passive — the measurement changes future collapse behavior.

10) Reference

Raul Sanchez Perez, Energy-Driven Cellular Automata (EDCA): Foundational Definition, Dynamic Space, and Conservative Properties, EDCAWorld, Jan 2026.

https://edcaworld.com/wp-content/uploads/2026/01/fundaments.pdf

Raul Sanchez Perez, EDCA–Quantum Uncertainty: Emergence of a

Measurement Tradeoff from Shell-Gated Collapse

and Spin-Directed Selection, EDCAWorld, Jan 2026.

https://edcaworld.com/wp-content/uploads/2026/01/uncertainty-with-figures.pdf